LOOKOUT Joins 50+ Newsrooms Calling for Charges Against Don Lemon, Georgia Fort to Be Dropped

After two reporters were arrested for covering a protest, more than 50 news outlets are demanding federal authorities drop the charges.

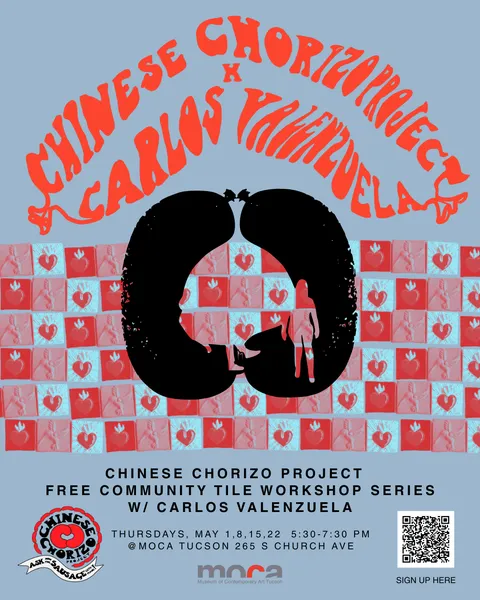

Chinese chorizo is being reborn in Tucson through Feng-Feng Yeh’s mission to preserve history, build visibility, and celebrate intersectional identity.

For decades Chinese chorizo was a staple food in Tucson’s Mexican and Chinese communities. But by the end of the 20th century, it had almost completely disappeared.

With the Chinese Chorizo Project, Tucson chef Feng-Feng Yeh wants to revive this once lost historical food.

Once a New York fashion designer, Yeh’s connection to Chinese chorizo is a story of homecoming and solidarity.

After years in the fashion industry, Yeh returned to Tucson during the pandemic. Finding a grant for community-based projects led her to think about her own community – one she said she had hardly learned of while in school.

Learning about the Asian community “was like not a thing, really, back then when I was growing up,” Yeh said. “I had felt really alienated.”

To find out about the role the Chinese community played in Tucson’s history was surprising to her.

Yeh discovered through the Tucson Chinese Cultural Center that Chinese grocers throughout Arizona had played a not-insignificant role in their communities, helping uplift their neighbors in times of economic hardship.

Yet, she found that these grocers and their legacies were lost to time, living on in only memories.

Yeh founded the Chinese Chorizo Project in 2021, bringing back a once-beloved food and reminding Arizona of its rich cultural history.

“To be able to carry a lost part of history is very powerful,” Yeh said.

Amidst discrimination and xenophobia, Chinese chorizo was formed out of partnerships between Mexican and Chinese communities.

According to the Tucson Chinese Cultural Center, Chinese immigrants first arrived in Tucson by the 1860s, first working as miners. Many would later become grocers or farmers.

Living under policies such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Chinese individuals faced violence and xenophobia.

Chinese-operated grocery stores, both in Tucson and Phoenix, became a crucial element of neighborhood life, providing valuable services such as credit to customers unable to immediately pay.

These Chinese grocers adapted to the Southwest, creating Chinese chorizo, which was often created from scrap meat and tailored to local tastes with Mexican spices.

“They really did try to cater to their community,” Yeh explained, describing the relationship between Mexican and Chinese communities as symbiotic. “I thought this chorizo thing was like this beautiful metaphor for this immigrant experience.”

Yeh said that after 1950, the number of Chinese grocers fell from over 100 to just five or less today, due to competition from larger grocers and owners encouraging their children to pursue other professions.

“They all became obsolete [...] they don't exist anymore like how they used to,” Yeh said.

With hardly anyone left to produce it, Chinese chorizo became lost in history.

In 2021, Yeh launched the Chinese Chorizo Festival in Tucson.

Alongside chefs Maria Mazon and Jackie Tran, Yeh said she prepared hundreds of pounds of meat and vegan chorizo, which was distributed to Tucson restaurants for them to make Chinese chorizo dishes.

Yeh didn’t expect to receive such a warm response.

“Lots of different people who I didn't know were coming up to me and telling me, ‘Thank you’ for being able to be seen,” Yeh said.

In recognition of Chinese chorizo’s significance to Tucson, in 2023, the Pima County Board of Supervisors named October ‘Chinese Chorizo Month.”

At the heart of the Chinese Chorizo Project’s mission is intersectionality, demonstrating how marginalized communities worked together in the face of oppression.

As a food borne out of solidarity between Mexican and Chinese communities, Chinese chorizo occupies a unique place in Arizonan history, which Yeh has leveraged to create educational opportunities.

“It helps to keep people thinking about the common threads that we have,” Yeh said.

One vehicle Yeh is utilizing to draw attention to these connections is public art.

In June, the Chinese Chorizo Project unveiled a shade sculpture in Eastlake Park as part of ¡Sombra! Experiments in Shade, a public art project designed to bring heat relief to Phoenix communities.

Once home to numerous Chinese grocers, Eastlake Park has significant ties to marginalized communities and the Civil Rights movement.

In preparation for ¡Sombra!, Yeh found that residents in historically redlined districts, like Eastlake Park, experienced higher rates of heat related deaths than those living in other Phoenix residential areas, a trend she said continues in the present.

“To be able to tell that story and make this link to how these racist practices have affected us, even into today, was really important,” Yeh said.

The shade structure pays homage to the shared history of Asian and Black communities in the area, highlighting significant figures like Wing F. Ong, the first Chinese American to be elected into state legislature, and pastor and civil rights advocate Warren Stewart, Sr.

“The foundation of us solving critical issues like the heat crisis is to actually appreciate and understand each other's histories and stories, good and bad, and to understand that we have been existing together,” Yeh said.

The Chinese chorizo shade structure will be on display until November.

At the surface, Chinese chorizo may just be food, but it represents the reclaiming of lost history and the active fight against erasure.

“I wasn’t taught this history,” Yeh said. “Had I known all of this history growing up, it would have changed my outlook on my own identity.”

As a queer artist and chef, Yeh’s work is part of a broader conversation about teaching intersectional history.

Historical records of Tucson’s LGBTQ+ history are sparse – Yeh said she’s consulted leaders in Tucson’s LGBTQ+ community and come up with few results, highlighting the need to keep the past alive.

“We have to continually check on [history] and take care of it, so that it doesn't get lost, so that people can continue to remember it and to learn from history,” Yeh said.

Reclaiming Chinese chorizo’s once-lost history is just one aspect of carving out space for queer Asian voices.

Yeh pointed to stereotypes and fetishization as a problematic aspect of the LGBTQ+ community that she hopes can be resolved with more representation.

“By doing work through Chinese chorizo or like just in general, having more voices of the Asian community within the LGBTQ community, I think it gives our community more depth and more range.”

Still, Yeh acknowledged that there is still more to be done for Asians in the LGBTQ+ community.

“I encourage the Asian LGBTQ community to really be vocal and really make your presence noticed,” Yeh said. “We just need to be heard. We need to have more presence.”

At LOOKOUT, we believe in the power of community-supported journalism. You're at the heart of that community, and your support helps us deliver the news and information the LGBTQ+ community needs to thrive.

LOOKOUT Publications (EIN: 92-3129757) is a federally recognized nonprofit news outlet.

All mailed inquiries can be sent to 221 E. Indianola Ave, Phoenix, AZ 85012.